A modern supply chain is more than the efficient movement of optimized inventory downstream to meet forecasted customer demand. Of course, this is a huge part of what it should do, but demand exists to be both met and steered.

Assortment, space and pricing decisions naturally play a part in the supply chain. In-store offers are increasingly built to address local need and ensure a pleasant customer experience — the product exists where the shopper wants to purchase it — but there is more to it than just meeting the customer on their terms. Given space constraints, the assortment carried has to balance customer need and shelf space. Not every store can carry every product.

The layout of the store and shelf position play a part in steering customer demand. Bright and colourful fresh foods are typically located near entrances to project a healthy image and promotions are often carried on shelf ends, while eye level is reserved for better sellers and higher margin products. It’s called the price ladder for a reason!

On a more immediate and local level, pricing can sway customers to try new products, switch to other brands or help move ageing products off shelves to make way for new inventory, while promotions are designed intentionally to increase demand for products at certain points of the year.

Each of the functional areas — inventory management, assortment & space and pricing — influence the other areas because they are all connected to customer demand. A price change can reduce inventory to the point where availability suffers; a move to the bottom shelf can disrupt inventory plans, and too much inventory can force a clearance.

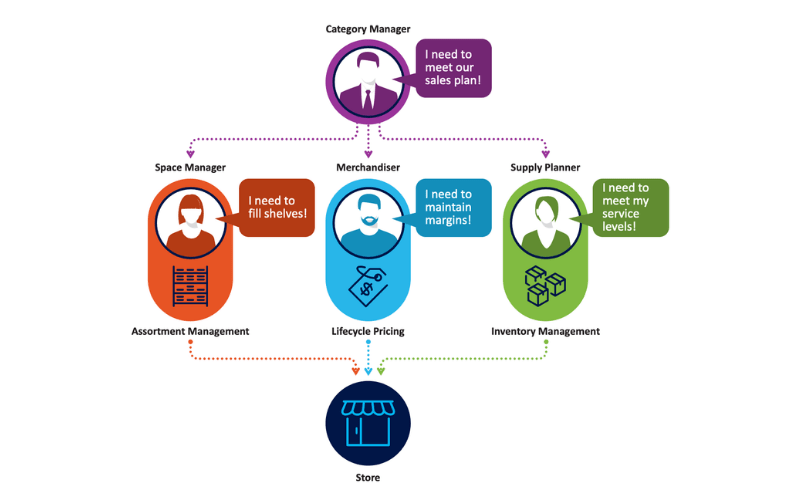

Many retailers operate like this today. A company strategy, often expressed in a sales plan, would cascade from the category manager to the functional owners in the category cell who would each interpret the direction within the sphere of their own influence. Space managers may increase inventory levels by maximum facings, pricing managers would try to keep inventory levels low to avoid markdown, while inventory planners may focus on presentation or meeting an SLA.

If we were to try to visualize this operational model, it would look something like this.

A structure like this might optimize within a functional area, but it fails to optimize for the whole. In order to be effective, the supply chain needs to orchestrate around customer demand. It needs to be synchronized.

Three Reasons to Synchronise Your Supply Chain

1. Processes are not linear

In reality, the supply chain is not a simple linear progression from defining an assortment to optimizing shelf layout, to managing price and receipt of inventory. There are natural feedback loops between fulfilling and steering demand. Price influences inventory, inventory influences price. Each day, minor changes in any area triggers reactions in other areas. The model is circular.

2. Functional areas are siloed

An operational model where functional siloes are supported by siloed technology is self-reinforcing. Functional areas continually react to decisions made by others that compromise their contribution to the plan. Each of these reactive decisions in turn compromise other goals, which in turn degrade the whole.

3. The customer is not the focus

In models where metrics cascade and split across functions, the only common reference point is the store rather than the customer. Retailers are forced into measuring margin loss and availability at the selling location, which further reinforces the model. If your only focus is sales and margin, it is easy to ignore the customer.

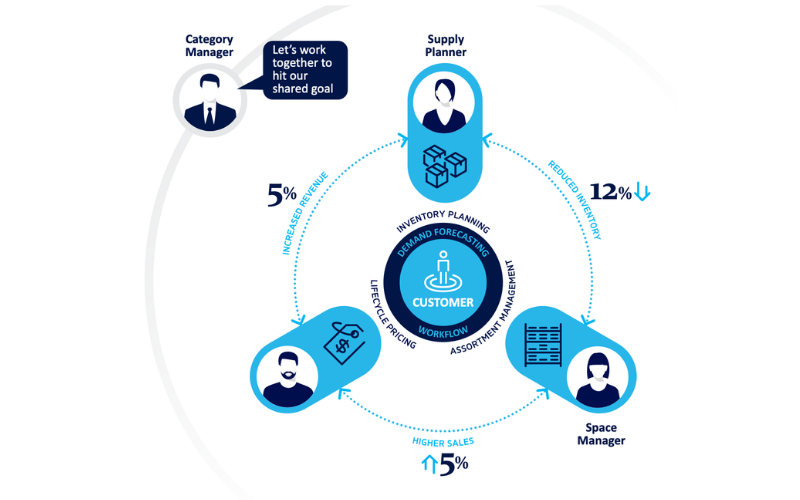

A Better Model Is Built Around Smarter Customer Connections

Shifting focus from store metrics to satisfying customer need is only possible through shared data. This allows functions to share a common view of impacts. A change in price is automatically reflected in inventory planning, which may in turn influence its position in the layout. Users become aware of the impact of their decisions outside their functions and genuinely collaborate. This is not to say that the expertise and specific competencies of each function should be lost, but rather that they need a means to coordinate activity.

Consolidating data on a single platform is a start but will only take you so far. Something needs to bind and coordinate the functional areas: a common source of demand.

By adopting one source of demand — a single intelligent and dynamic algorithm across all horizons — and sharing it among functional areas, you can preserve the rigor and expertise in each functional area while exposing the impacts of decisions cross functionally and ensuring that they are automatically executed in other areas. From a user perspective, a common user experience completes the picture, as the shared data pool can expose metrics typically outside the reach of a point solution.

Our transformed our model would look more like this.

This shift is only possible by adopting a genuinely intelligent and dynamic demand planning engine. My previous blog on Blue Yonder’s machine learning (ML) demand planning engine describes how probability and uncertainty can be baked into an automated demand planning process, and drive a supply chain transformation built around the customer. Demand becomes the glue that binds the retail operation. Based on intelligent and automated demand, the synchronised supply chain delivers greater speed and resilience, while improving results by optimising across the whole supply chain.

If you’d like to learn more, please download our e-book.