I have been an Agile enthusiast and a flag bearer for Agile methodologies for more than a decade now. Having worked with multiple IT giants and market leaders in the technology industry, I have had my share of opportunities to work in different project management models, and, needless to say, it’s how Agile takes the front seat in solving problems in the world where change is considered to be the only constant. I have talked about how Scrum, Kanban and Scrumban (a hybrid approach of Scrum and Kanban) have been a boon to tech-humankind in my previous papers and the benefits one can reap from the same to make their customer delivery experience an ultimate delight.

Having said that, there is one concept in Agile that continues to dissatisfy me when it comes to planning and delivering things in an agile manner — story points. My experience with story points has been delusional for a significant part of my experience and I can’t help myself from being the critique about the same. I am sure a lot of Agile Pandits are going to disagree with me as story points continue to be the ultimate source of the majority of the reports like burndown, burnup, etc., but we need to look at the things that it is making us compromise on as we go along.

Isn’t the core of being Agile about being able to cater to the changes and adapt to the need of the hour when required? And if so, aren’t story points which in turn are creating the team velocity, restricting the team to take up more challenges than yesterday?

Agile teams are considered to be self-driven and self-motivated, and if they are not achieving more than what they did yesterday, they are either not agile or not motivated enough or they are just following the agile velocity. Confused? Wasn’t velocity the primary factor to challenge the teams on their achievements in the first place? Indeed, but is the velocity really motivating them or binding them to a certain number, is the question we need to ask today. Most of the time I see that my team is under the impression that we need to pick the amount of work which is equal to the velocity of the last sprint. I wonder, if we continue to do so, how are we improving? How are we catering to the new changes and still deliver our priority items when needed? And most of all, how can something that was done in past be similar to something to be done in future?

Ron Jefferies, the creator of story points, has eventually agreed himself that creating story points was a mistake. He said:

“I like to say that I may have invented story points, and if I did, I’m sorry now.”

One of the most important aspects of story points caters to team velocity which in turn helps the product owners and the development team to estimate the work to be done in the future. By saying so, are we trying to predict the future? Is the future really that consistent? Don’t the variables change every time or are we just conveniently ignoring them?

In my experience, I have seen multiple sprints underestimated because the team’s efficiency was better on a story estimated with the same points as that of another one in the past or overestimated because what the team felt was a three-pointer ended up being a five or an eight because a piece of code – which seemed to be a regular drill during the estimation – turned out to be a little quirky with its unknown complexity or it decided to not play along with its counterpart when integrated. The explicit and implicit knowledge can probably give the team a fair idea about how to implement a use case and the time required to do that, but the integration of that code with the rest of the system is a maze of unknowns.

„If it’s just about estimating, why can’t we be more precise and just estimate in hours? Wouldn’t we be more efficient that way,“ I asked in an Agile conference. The answer I received was that story points take into account the required unknown buffer and allow more freedom to the development team. I think they just wanted to consider an unknown buffer to an hourly estimate to make sure that the team completes everything that they take up.

Most of the teams I or some of my colleagues have worked with relate their story point estimate directly with the hours eventually. I asked a development team member how they arrived at an estimate in one of our grooming calls and he responded that based on the complexity of the work he calculated the hours that are needed to code the bit and then added a 10% buffer to it. That number was closer to the particular estimate that he had hence quoted. Now every work that ranges between 2 to 8 hours has the same story point estimate and likewise anything that is between 17 to 32 hours may have the same story point estimate in a team. I have noticed different developers in the same team estimating the same story points to different effort of work in terms of hours.

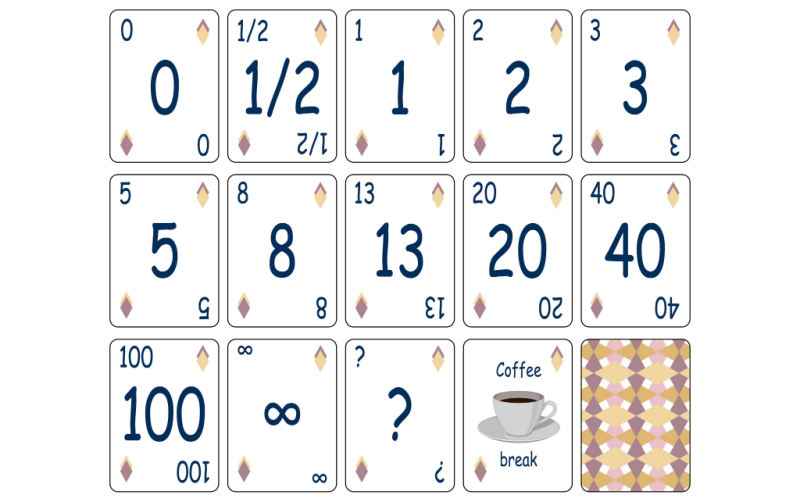

Absolute value estimation, according to me, is an utter waste in Agile. Estimating different work in multiples of a fixed amount of time, which in many cases is one day, is abusing the flexibility that Agile provides. To add to it, following the Fibonacci in an absolute world of estimations is a grave mistake. The combination of story points with the Fibonacci series is a hole dug so deep that you wouldn’t want to take a dive. I fail to understand why a piece of work must be at least double or triple the effort of the base value? Why can’t it be 1.3 or 1.7 times bigger? Is it because we don’t have a story point for that relation? It is funny how we have been consistently over/under estimating tickets because of this reason.

The relative approach can still take merit only if the base value is taken as minimally as possible.

Yet another problem I have with the story points is: who is giving these estimates? Are they really coming from the development team who is responsible for burning them? Or have you also encountered Scrum Masters and product managers who define or influence these points? Product managers, of course, need any piece of work to be as cheap as possible for they can pull in more work in the given budget. Scrum Masters often guide the team to the desired answer rather than let the team arrive at their answer based on conversation and understanding of the work. Even worse, I have witnessed several Scrum Masters declaring the story point value once the story is read. I think the Scrum Master’s decision comes from the delusion that they believe their tacit knowledge can help the indecisive development team to come to a better conclusion.

Even when the development team is providing the story point estimate, how many of these teams consider the QA effort along with the development effort in their estimates? I have had a chance to work with some good organizations who actually do that, but from the majority of my experience I would say the number is much less. I have in fact seen teams requesting a totally separate story for QA for all their functional development work and having its own story point effort. This QA story is picked up after the development story has been closed altogether and a testable build is provided to QA. Doesn’t that sound like a mini-waterfall model with an additional coating of timebox?

All in all, the concept of story points is very gloomy and has been adopted by different teams in their own customized way.

A few conversations that we encounter almost every day are:

- “Story points are about complexity”

- “One story point, what does it relate to?”

- “Should we estimate/put story points to bugs?”

- “Spike stories, can they have a buffer? They are very time-boxed events and defy the story points concept.”

It is funny how story points have become a factor to gauge the success of a team unknowingly. Irrespective of the value being delivered in a sprint, what some of the product managers are looking for is the amount of story points being delivered each sprint. And if a team has delivered more story points than their previous sprint, they celebrate it as a success. It’s like a magician focusing on showcasing more tricks rather than the ones that would actually have the crowd mesmerized.

Tell me how many of your retrospectives have had questions like:

- “Our burn down looks bad; we did a bad job this sprint. Why?”

- “Why did we deliver less than our velocity this sprint?”

- “The team velocity has become stagnant; how can we improve it?”

- “We are spilling out a lot of stories, how can we make sure we complete what we pick?”

Ron Jeffery, when asked if creating story points was really a mistake, said:

- I certainly deplore their misuse;

- I think using them to predict “when we’ll be done” is at best a weak idea;

- I think tracking how actuals compare with estimates is at best wasteful; and

- I think comparing teams on quality of estimates or velocity is harmful.

Conclusion:

Story points as a concept is not really a mistake per se, but the way engineering teams have customized and adopted them in their own way is doing more harm than good to the teams in multiple ways. I think we can avoid many pitfalls by avoiding story points and still not having to micromanage things. I created a “colored cards” technique (which I will talk about in detail in my next paper) in one of my teams and it seemed to deliver more value each sprint than what we do with story points. I do not mean to advise boycotting the story points, rather look for innovative approaches to deliver more value each sprint and try to be more agile to be able to cater to ever changing needs of clients. If story points are doing just fine for you to achieve that, well, please carry on with them.

About the Author:

Siddhartha Garg is a Project Management Professional at Blue Yonder and likes to call himself an Agile evangelist while boasting more than 11 years of experience in the Agile world of development. He likes to describe himself as a dynamic, forward thinking, and amiable Product Manager in IT services and Product, driving the success of multiple large-scale products from e-commerce, health, IP, food delivery, travel, entertainment and EdTech domains. With certifications in Scrum and PMP after completing B.Tech in IT and MBA in IT Operations from IMT University, he loves to create new customer-centric, sustainable IT products that cater to the pressing needs of the customers. An ex-entrepreneur and published author of a national bestseller, he has always been keen in writing about topics that can help to contribute something to the society or a large population on humankind